The fate of the island of Melos in the Peloponnesian War illustrates the risk to the weak of believing they can remain neutral when the fighting is raging all around them.

In Book V of the History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides presents a dialogue between Athenian ambassadors and Melian notables (V, 84), known as the Melian dialogue, or the dialogue between Athenians and Melians.

Melos is a small island in the Aegean Sea. Its location would allow whoever ruled it to act effectively on maritime traffic. It was therefore a key position for Athens, which depended on the tribute paid by its allies (see our article The thalassocratic system in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War). The city chose to remain neutral in the war that had been raging between Sparta and Athens for 15 years.

In 416 BC, the Athenians felt that the neutrality of this small city represented too great a risk and decided to give it an ultimatum: submit to the Empire or see their city destroyed. After all, the Melians are also Sparta’s colonists. An edifying dialogue ensues between Athenian delegates and Melian notables.

Melos’ neutrality rejected

Melos offered to remain neutral. This argument was immediately rejected by the Athenians.

“your hostility does us less harm than your friendship: the latter would appear in the eyes of the peoples of the empire as proof of weakness, your hatred as proof of power”.

Athens based its power on the tribute it received from its subjugated cities. It therefore had to ensure that it dominated the sea routes. If it accepted that Melos should remain neutral, it opened the door to demands from other island peoples.

The heart of the Melian dialogue: right versus possible

The Athenian delegates began by dismissing the legal argument.

“we’re not going to […] use big words, saying that having defeated the Mede gives us the right to dominate, or that our current campaign stems from an infringement of our rights”.

They intend to rely on power relationships.

“If the law intervenes in human assessments to inspire a judgement when the forces are equivalent, the possible, on the other hand, governs the action of the strongest and the acceptance of the weakest”.

For the Melians, it’s submission or death, whatever their legal position. “Either we prevail in terms of the law, refusing to give in, and it’s war, or […] it’s servitude”.

Destruction of Melos

Strengthened by their right and the divine support that goes with it, the Melians chose to resist despite the power of Athens. They counted on Sparta to come to their aid.

“In the name of their own interests, they will not want to betray Melos, a colony of their own, in order to become suspect to their supporters in Greece and do their enemies a favour.

But Sparta did not make a move. After all, Melos never took their side. Melos’ position was irrational.

“Your strongest support comes from a hope for the future, and your present resources are meagre to successfully resist the forces now arrayed against you”.

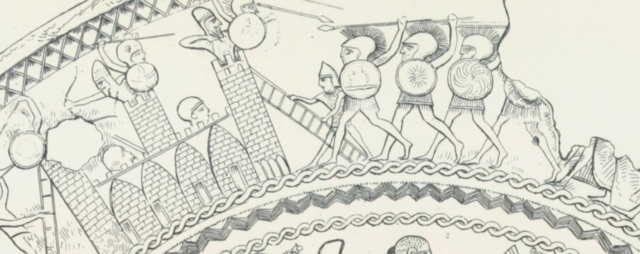

After several months of siege, Melos, starving, tried to negotiate its surrender. But the Athenians proved implacable. They subjected the city to extreme violence, even for the time. They slaughtered the men, took the women and children into slavery, and then brought in their own colonists. The fate of Melos left a lasting impression on the Greek world. Because it thought it was choosing honour, relying on neutrality and help of a power that was culturally close to it, it ceased to exist.

Right, morality and power

What conclusion is to be drawn from the Melian dialogue? Not that might makes right. But that despite the rule of law, power relationships do not disappear. They must be taken into account. Morality carries little weight in the face of what a player perceives to be his vital interest. And like promises, alliances are only binding on those who believe them.

Read also Ares and Athena, Gods of War