Many cultures have their own god of war, but this function is often tied to other roles. This shows us how each culture perceives war. Here’s an overview of the main war gods from different cultures around the world. The list is, of course, not exhaustive.

Western Europe : Tension between brutality and intelligence

Roman mythology – Mars, god of war

Mars , the Roman god of war, was more than just a god of violence and conflict. His role in society was significant, both military, agricultural, and civic. Mars embodied the Roman ideal of discipline, strength, and justice. As the protector of soldiers and guarantor of borders, he played a vital role in Roman public life. His function also extended to agriculture and the founding of colonies, illustrating the importance of warfare to the preservation and expansion of the Roman Empire. Read more.

Ares, god of war and violence

Ares, the Greek god of war, is an emblematic figure of ancient mythology. Worshipped mainly in Greece, he embodies the violence and brutality of conflicts. His attributes include weapons and animals symbolizing strength and aggressiveness. Ares represents the destructive and chaotic aspect of war. He is opposed to Athena, who symbolizes strategy and wisdom. He is associated with bloody and disorganized battle. Read our full article.

Athena, goddess of intelligence in war

Athena , goddess of war and wisdom, is a central figure in the Greek pantheon. Representing strategic intelligence in conflict, she was worshipped in several city-states, including Athens. Her attributes include the aegis, spear, and owl. Unlike Ares, who symbolizes brute violence, Athena embodies a thoughtful and tactical approach to warfare. In addition to her martial skills, she patronized the arts, justice, and crafts, reflecting her versatile role in Greek mythology. Read the article.

TEUTATES, GALLIC god of war AND fertility

Teutates was one of the most revered gods of ancient Gaul. His name means “the god of the tribe” or “the protector of the people.” A versatile deity, he represented both war and fertility, two areas essential for the survival and prosperity of the tribes.

As a god of war, Teutates was often associated with Mars, the Roman god of war. This reflects an adaptation of Gallic beliefs in the face of Roman influence. Rituals dedicated to this god were sometimes marked by human sacrifices, testifying to the fervor and gravity of these practices. Victims were often drowned, a form of sacrifice that aimed to appease this demanding deity and gain his support.

Teutates was not only a warrior god. As a fertility deity, he also watched over the crops and prosperity of the people. His protection thus extended well beyond the battlefield, symbolizing the strength and unity of the Gallic tribes. Each tribe had its own cult dedicated to Teutates, which reinforced the collective identity and sense of belonging.

The cult of Teutates gradually disappeared with the Romanization of Gaul, but it remains today a powerful symbol of Celtic culture.

Camulos, Celtic god of war

Camulos , the Celtic god of war, was worshipped in ancient Gaul and Britain for his military power and protective role. His cult spread far beyond the Celtic lands, becoming part of various regions of the Roman Empire. This spread is evidence of Camulos’ importance to warrior populations.

Like Mars, Camulos was a symbol of military strength and protection. The Romans often depicted him with similar attributes: an imposing helmet, a sword, or a shield, which referred to his martial nature.

Camulos was not only a god of war. He also embodied the sovereignty and legitimacy of the chiefs, who invoked his name to reinforce their authority. The rituals in his honor were aimed at ensuring victory but also at guaranteeing the prosperity of the tribes. This aspect proved crucial in societies where war and fertility were closely linked.

Despite the progressive Romanization of Celtic territories, the figure of Camulos has managed to survive. It has become a bridge between local traditions and Roman influences. Its image, combining warrior strength and sacred power, remains today a testimony to the beliefs and values that animated the Celtic peoples in search of protection and prosperity.

Sucellos, war, fertility and forge

Sucellos was a complex Celtic deity, worshipped throughout Gaul. While he was often associated with fertility and blacksmithing, his role extended far beyond these domains. He embodied the duality of creative and destructive power. His powerful image made him a deity honored by blacksmiths and warriors alike.

One of the most characteristic symbols of Sucellos is the mace he carries. This object, both tool and weapon, symbolizes brute force but also the ability to shape and transform. As god of the forge, Sucellos was the patron saint of artisans. They shaped weapons and tools, essential elements for daily life and wars. His association with the forge directly links him to the earth and natural resources, sources of fertility and wealth for the Celtic peoples.

But Sucellos was not only a god of life and creation. His mace, a symbol of destruction, also gave him a warrior role. He was invoked to protect communities during conflicts and to ensure the victory of tribes in battle. His ability to destroy as well as create made him a fearsome figure, capable of maintaining the balance between peace and war. This dual nature, both nurturing and destructive, reflects the Celtic conception of the universe, where opposing forces coexist and complement each other.

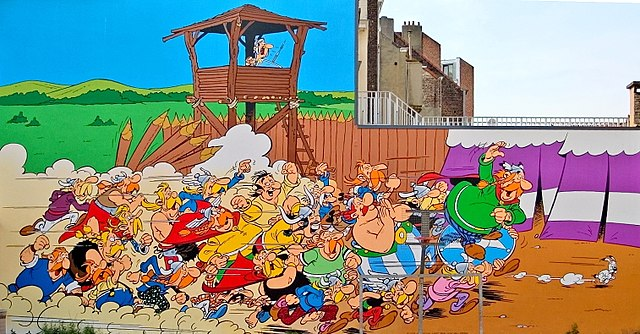

contemporary france

Asterix and Obelix are the main icons of French warrior culture. Imagined by the creator gods Goscinny and Uderzo, they have become warrior symbols. They represent the resistance and bravery of the French. Their fighting spirit and perseverance make them models for strategists and soldiers.

Asterix, a clever little warrior, embodies tactical intelligence. He stands out for his ingenuity. His strength lies in his ability to thwart enemy plans. Asterix proves that a quick mind can beat the greatest armies. His cunning makes him a formidable strategist.

Obelix, at his side, is brute force. His imposing stature and power make him formidable. Thanks to the magic potion, he has unmatched strength. Obelix is the image of French solidity and resistance. He symbolizes robustness in the face of adversity.

Together, they form an invincible duo. Their complicity illustrates solidarity in the fight. Asterix and Obelix represent the unity needed to win. Their only fear? That the sky will fall on their heads.

Norse mythology – gods associated with war

Thor is the god of thunder, lightning, and protection in Norse mythology, but he also plays an important role as a warrior god. Although Odin and Týr are more specifically associated with war, Thor is often invoked by warriors for his unmatched strength and destructive power. He fights giants, the enemies of the gods, and protects humanity with his famous hammer, Mjölnir . He represents bravery, raw power, and the defense of order against chaos.

Odin (Norse mythology). Although he is a god of wisdom, Odin is also often invoked by Viking warriors to guide them in battle.

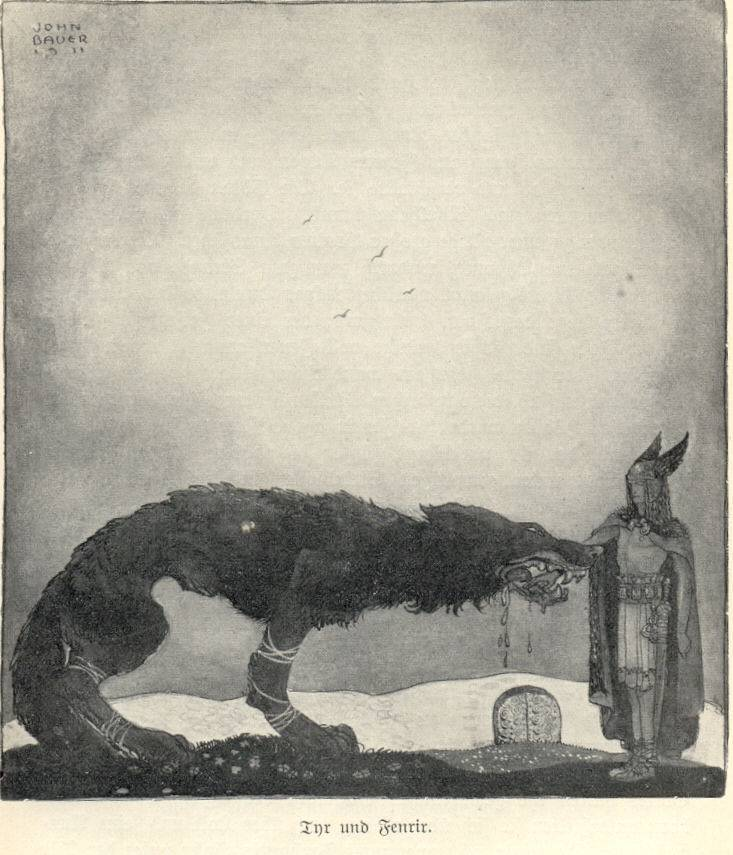

Týr, god of war, courage, honor and justice.

Týr, the god of war in Norse mythology, embodies courage, honor, and justice. Unlike other warrior deities, Týr symbolizes war as an act of justice, where honor and loyalty prevail. The Vikings revered him for his bravery and righteousness in battle.

Týr does not fight for violence, but for justice and fairness. His role therefore goes beyond mere warlike confrontation. He represents war as a means of restoring order and protecting fundamental values. His courage inspires those who seek to defend the truth.

The Sacrifice of Tyr

Týr is best known for his heroic act of sacrifice. According to Norse mythology, Fenrir, a gigantic and dangerous wolf, was destined to cause great destruction. The gods, concerned about his power, decided to chain him up.

Fenrir, wary, refused to be bound unless one of the gods proved his good faith by putting his hand in his mouth as a token of trust. Knowing the danger, Týr accepted this sacrifice. When the gods managed to bind Fenrir with an unbreakable magic chain, the wolf, enraged, tore off Týr’s hand.

This heroic act symbolizes Týr’s courage and honor. He was willing to lose his hand to protect others, showing his deep sense of duty and justice. This gesture reflects Týr’s nature, ready to do anything to protect others and ensure cosmic balance. This story also reflects the theme of sacrifice necessary to maintain order in the face of chaos.

Týr remains a central figure in Norse mythology, where his strength, honor, and sacrifice make him a role model for warriors. Týr also symbolizes fighting with rig

West Africa: Gods of War and Metal

Ogun, god of war and iron

Ogun , god of war and iron, is a major deity in traditional African religions. Revered in West Africa and the diaspora, he embodies brute force, power, and the ingenuity of metallurgy. Ogun is distinguished by his mastery of iron, which he transforms into weapons and tools. The latter are symbols of progress, but also of destruction.

Ogun’s attributes include iron tools and weapons, representing his technical mastery. Animals, such as the dog and the leopard, are often associated with his worship to illustrate his strength and determination. In rituals, followers pray to him for victory, protection, and justice. Despite his association with war and violence, Ogun is not only a destroyer. He is also the guardian of hunters and blacksmiths, ensuring the balance between creation and destruction.

Ogun is also revered as a god of justice, punishing injustice and protecting the oppressed. His role in traditional African societies therefore goes beyond mere warlike violence. He embodies order, protection and law. Ogun embodies the duality of war: both destroyer and protector, ensuring order in chaos. Read our article.

Gu, war and forge

Gu , the god of war, has been venerated in the Voodoo cultures of Benin and Togo for centuries. He is closely linked to the forge and weapons. He plays a protective role for warriors. His attributes, such as iron, hammer and anvil, symbolize his power over metals and his ability to forge the tools of war. He embodies the strategic and creative aspect of conflict, while having other attributions in protection and metalworking. Read more.

Egypt: A lioness woman goddess of war

Sekhmet (Ancient Egypt) is a goddess of war, destruction, and healing in Egyptian mythology. She appears in the form of a lioness, symbolizing her ferocity in battle. According to myths, Ra, the sun god, sent her to punish humanity, and she nearly exterminated humanity in her fury. However, she is also a healer, able to cure diseases, making her a complex deity, combining war and healing. Read the full article.

hteousness and justice, an ideal that the Vikings sought to embody on the battlefield.

Asia , some gods of war

India, INDRA, king of gods and god of war

Indra, king of the gods in Hinduism, embodies war, storms and the sky. He reigns over the deities and imposes his authority on the universe. Ancient Vedic texts, such as the Rig Veda, recount his exploits as defender of the heavens. Indra stands as the shield of cosmic order.

He relentlessly fights the forces of evil, especially demons, whom he defeats with his formidable weapon, lightning. He is famous for having defeated Vritra, a serpent-demon who held back the waters of the world. Thanks to this victory, Indra freed the rivers, thus ensuring the survival of living beings.

The storms he controls symbolize his power. Indra can indeed make rain fall and nourish the lands. His role is essential to maintain the balance between heaven and earth.

Beyond war, Indra also protects humans. He thus grants his favors to those who honor him. Warriors and kings, in particular, paid him homage to obtain his blessing. Through his courage and strength, Indra establishes himself as the champion of good, thus guaranteeing the stability of the universe in the face of chaos.

India, Kartikeya, celestial commander

Kartikeya, the Hindu god of war, commands the celestial armies. He embodies victory, youth and courage. This son of Shiva and Parvati is a formidable warrior, revered for his strength and bravery.

He leads the gods into battle against the forces of evil. His weapons, often represented by a spear and a peacock, symbolize his power and control. Kartikeya defends good against the demons, thus ensuring the victory of the divine forces.

Kartikeya is not only a warrior. He also inspires youth and vitality. Young men, in particular, revere him as a model of courage and discipline. His eternal youth makes him close to the faithful, who seek his protection and guidance in difficult times.

His role extends beyond the battlefield. Kartikeya is also the guarantor of justice and order in the celestial world. He ensures that balance is maintained between the forces of good and evil.

Thus, Kartikeya embodies both warrior strength and life energy. Through his victories and fighting spirit, he remains a model of courage and endurance for those who seek victory and justice.

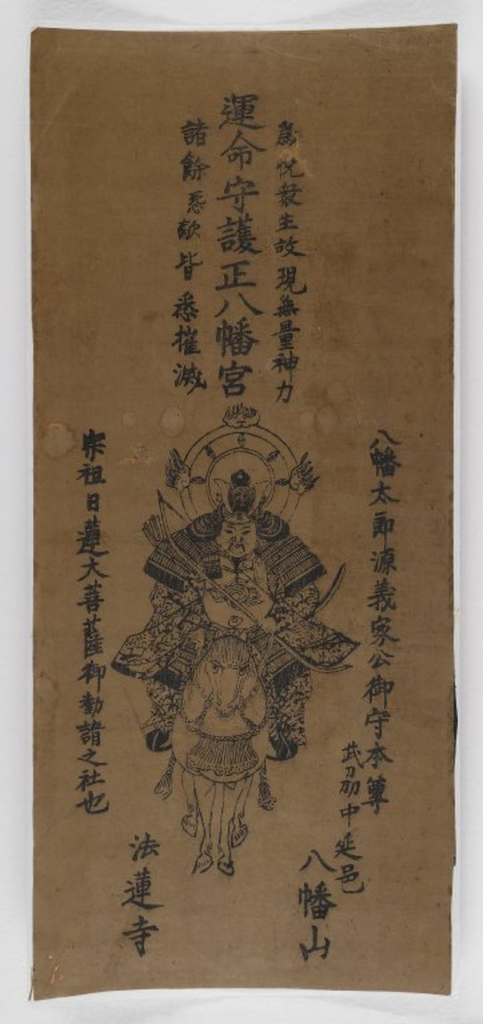

Japan: Hachiman, god of war

Hachiman, one of the most important deities in the Shinto pantheon, is the god of war in Japan and the protector of samurai warriors. His veneration dates back to the time when the samurai dominated the warrior class, representing courage, strength, and honor. Hachiman is also considered the spiritual guardian of Japan, responsible for protecting the archipelago from external threats and ensuring the country’s prosperity.

This god is often identified with Emperor Ōjin, with whom he sometimes shares the same identity. His cult quickly spread throughout Japan. More than 30,000 shrines, called Hachimangu, were dedicated to him. He thus became one of the most popular Shinto deities. Samurai paid homage to him before each battle. They hoped to obtain his blessing for victory and protection.

Hachiman does not only embody war. He also plays a role in fertility and the protection of crops. This reinforces his place in Japanese society. A complex deity, he symbolizes both war and peace.

PERSIA, AResha, God of victory and justice

Aresha , the god of victory and justice in Zoroastrianism, symbolizes balance in the midst of conflict. He also embodies the force that triumphs over chaos and restores order. The Persians revered Aresha for his power to ensure divine justice in a world plagued by disunity.

Aresha is not only a celestial warrior. He also represents moral triumph. The faithful venerate him for his principles and his ability to maintain a just cosmic order. He is the protector of souls who fight for the truth.

As the deity of victory, Aresha ensures that justice always prevails over deception and violence. Her presence is a reminder that justice and balance are the keys to overcoming chaos. Through her role, she represents moral strength and righteousness in the midst of conflict.

CHINA: Chi you, warlord, god of war

Chi You , an ancient warlord and god of war in Chinese folklore, embodies brute force and military strategy. He is famous for leading numerous rebellions and for his epic battles against the imperial forces. Chi You symbolizes the power and indomitable spirit of warriors.

With his martial skills and supernatural powers, Chi You was a feared and respected opponent. But beyond battles, he also embodied rebellion against oppression. For many Chinese, Chi You thus represents resistance and the quest for justice against the powers that be. His courage inspires those who defend their freedom.

The Battle of Zhuolu

He fought the Yellow Emperor, a legendary figure of ancient China, in the famous Battle of Zhuolu. This fight has remained engraved in history as one of the greatest mythological clashes.

Although defeated, Chi You was deified and revered as the god of war. He remains a prominent figure in Chinese folklore, illustrating the importance of courage, strength, and resilience in the face of adversity. Through him, the story of China’s great warriors continues to live on and inspire.

According to legend, Chi You, endowed with supernatural powers and a formidable army, had the upper hand at the beginning of the battle. However, the Yellow Emperor, aided by ingenious strategies and advanced technologies, managed to prevail. He is said to have summoned spirits and used a compass to counter Chi You’s magical mists, which allowed him to triumph.

The Yellow Emperor’s victory over Chi You symbolizes the triumph of order over chaos, and marks the founding of an era of civilization in ancient China. Read the rest of the article.

Middle East , gods of war and destruction

Anat, destruction and creation

Anat , the Phoenician goddess of war and fertility, is a formidable and complex figure. Known for her power and aggression, she embodies destruction on the battlefield. The Phoenicians revered her as a relentless warrior, capable of sowing death among her enemies.

In mythological tales, Anat is often depicted as fighting mercilessly, ravaging opposing armies. Her ferocity makes her invincible, and she embodies the brute force necessary for victory. The gods themselves respect her for her ability to restore order through violence. Anat thus plays a vital role in maintaining cosmic balance.

However, she is not only a warrior goddess. Anat is also linked to fertility. Her duality reflects the idea that destruction and creation go hand in hand. She ensures the continuity of life after battle. Her role as protector of the cycles of life counterbalances her violent nature.

Revered throughout the Levant, Anat is a symbol of feminine strength. She embodies both war and rebirth, making her an essential figure in Phoenician mythology, where she combines destruction and fertility in a fearsome harmony.

Nergal, Mesopotamian god of war and the underworld

Nergal , the Mesopotamian god of war and destruction, also rules the underworld. He embodies violence, epidemics and chaos. In Mesopotamian mythology, Nergal is therefore a feared figure, often associated with death and the plagues that ravage peoples.

He leads the heavenly armies with unmatched brutality. His destructive powers strike terror into his enemies, whom he mercilessly destroys. Nergal does not hesitate to use violence to restore order, even if it means plunging the world into chaos. The ancient Mesopotamians prayed to him to avert war and calamity, while fearing his wrath. They often depicted him as a lion.

His connection to the underworld reinforces his image as a destroyer. Nergal reigns over the dead, ruling the underworld with absolute power. He is also associated with the spread of epidemics, which he uses to weaken mortals.

Despite his fearsome appearance, Nergal plays a necessary role in the cosmic balance. He embodies the destruction necessary to make way for renewal. His presence reminds us that chaos and violence are an integral part of the world’s order, just as life and death are.

America , celestial figures

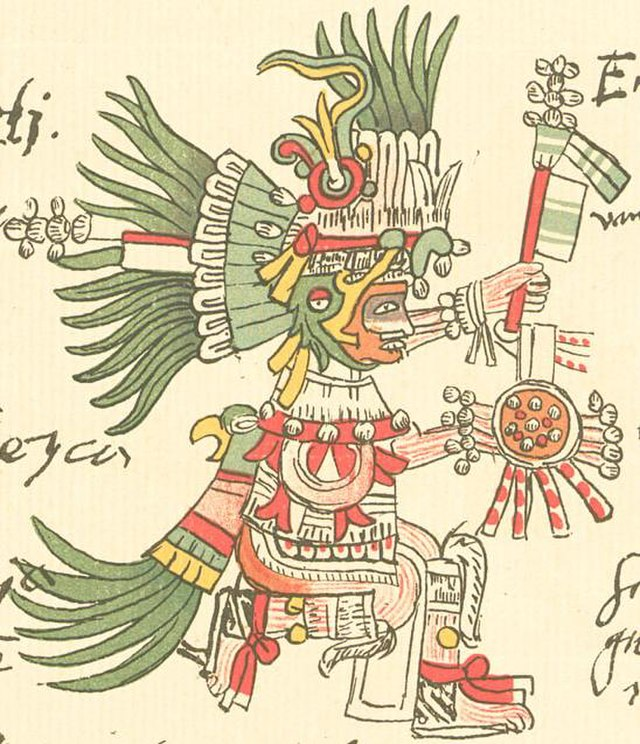

Huitzilopochtli: Aztec god of war and the sun

Huitzilopochtli , god of war and the sun, was the patron of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztecs. Considered the protector of the Aztec people, he embodied victory and military power. Huitzilopochtli was linked to the cosmic order, requiring human sacrifices to ensure the balance of the world.

According to mythology, Huitzilopochtli was born on top of the Serpent Mountain, Coatepec. From the moment he was born, he triumphed over his enemy brothers and sisters, thus proving his warrior nature. This legend quickly placed him at the heart of Aztec beliefs, making him a feared and venerated god. Human sacrifices, often practiced at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, were intended to offer him the strength necessary to fight the darkness.

Huitzilopochtli was depicted with warrior attributes: a spear, a shield decorated with feathers, and brightly colored clothing. His image embodied the sun in motion, traveling across the sky to repel the forces of chaos. Festivals in his honor, such as the Panquetzaliztli, punctuated the religious life of the Aztecs and strengthened their social cohesion.

Huitzilopochtli symbolized warrior determination and the duty to protect cosmic balance. His legend has survived the centuries, recalling the importance of war and sacrifice in Mesoamerican culture.

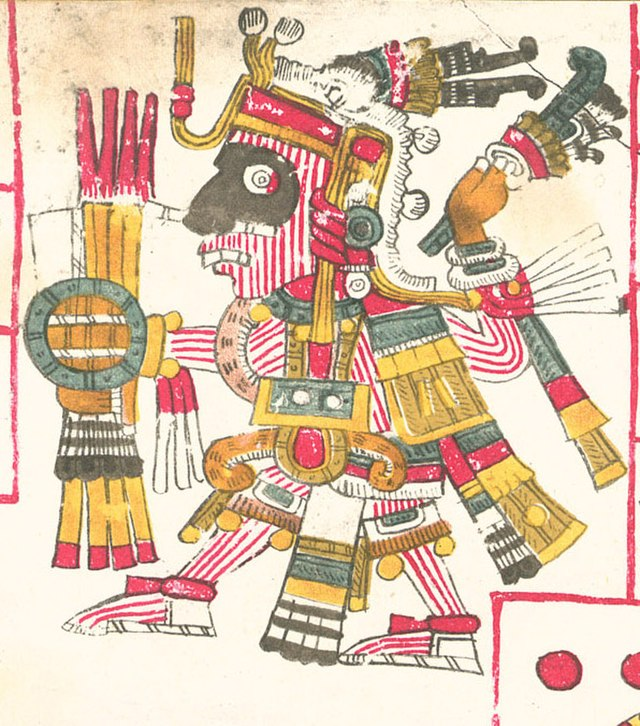

Texcatlipoca

Tezcatlipoca , one of the major deities of the Aztec pantheon, is primarily known as the god of the night and stars. However, his influence extends beyond the nocturnal sphere. He also plays an important role in conflicts and war intrigues. Considered a complex and mysterious god, Tezcatlipoca embodies both destruction and regeneration, war and magic.

In Aztec mythology, he is often associated with deception, discord, and power struggles. Tezcatlipoca is described as a skilled strategist, able to manipulate his enemies and sow confusion. This ability to orchestrate conflicts made him a feared and respected god. In particular, he could determine the outcome of a war thanks to his ability to influence the destiny of men.

Tezcatlipoca possesses a number of attributes. His obsidian mirror is a symbol of vision and clairvoyance, but also of war and destruction. This mirror allows him to see the past, present and future. It thus gives him an almost omniscient power over human events and decisions.

For the Aztecs, honoring Tezcatlipoca meant seeking divine protection in battle, while accepting the uncertainties of war. His figure recalls the importance of cunning and courage, qualities essential for survival in a world where brute force was not the only path to victory.

Mixcoatl Aztec god of hunting and war

Mixcoatl , an Aztec deity, was worshipped as a god of hunting and war. His name, meaning “cloud serpent,” evokes his connection to the stars and celestial paths. This cosmic association made him a guide for warriors and hunters.

According to mythology, Mixcoatl was the father of many gods, including Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent. His legend is marked by episodes of struggle and conquest. As a warrior god, he embodied the spirit of the hunt and battle. His followers believed that his powers helped them navigate the darkness and thwart the traps of their enemies.

Mixcoatl was often depicted with hunting attributes: bow, arrows and deer skin. These elements emphasized his protective role towards those who lived from hunting.

Mixcoatl was also linked to celestial phenomena. He symbolized the Milky Way, which was considered a sacred path for the souls of the deceased. The stars, in particular, played an important role in his cult, illustrating his ability to guide and defend.

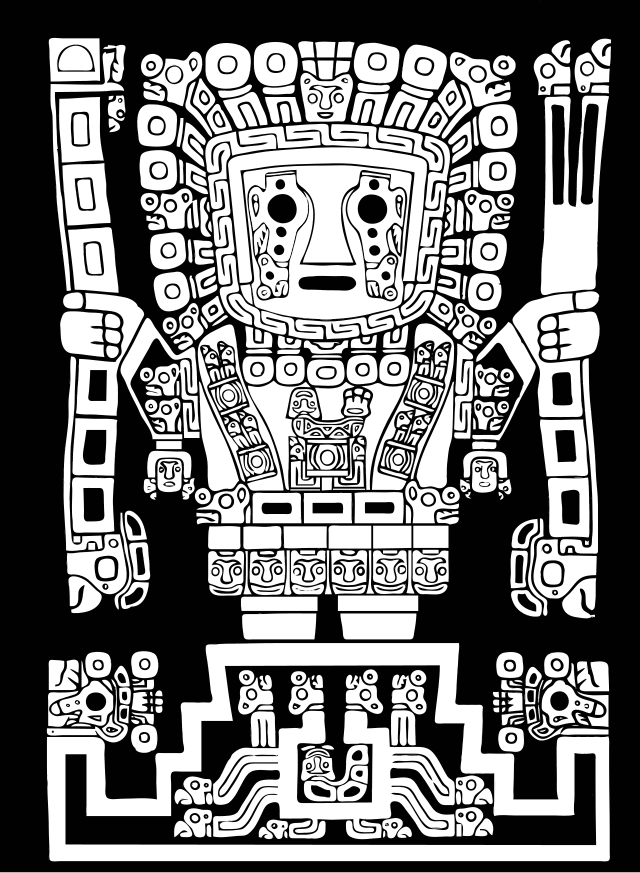

Viracocha: creator god and warrior of the Andes

Viracocha , a major deity of the Incas, was the creator god and a powerful warrior. He was considered the one who shaped the world and human beings. However, his role was not limited to creation. Viracocha was also a conqueror, fighting against darkness to establish cosmic order.

Legend has it that Viracocha emerged from the primordial waters, bringing light and life to a world of chaos. With his divine power, he created mountains, rivers, and the skies. He then shaped humanity, teaching them the laws of life and civilization.

However, faced with the forces of disorder, he had to take on a warrior role. Inca myths describe him as a wise but fearsome god, capable of unleashing storms and lightning to restore balance.

Viracocha was often depicted with attributes of creator and warrior: a staff or scepter to symbolize his power, and rich clothing, decorated with celestial motifs. His imposing presence recalled his duality, between generosity and destruction. The Incas venerated him as the guarantor of prosperity, praying that he would maintain order in the face of the threats of chaos.

Viracocha, by combining creation and war, illustrates the importance of cosmic order in Andean culture. His legacy, still present in local traditions, testifies to the depth of his legend.

Oceania – Gods of War

Ku, god of war and fishing in Hawaii

Ku , the Hawaiian god of war, represents strength, virility and victory. His cult extends throughout the archipelago, particularly during times of war. Hawaiian warriors invoke him by offering sacrifices, some of which are human. Indeed, these rituals aimed to obtain victory in exchange for bloodshed. Furthermore, Ku embodies brutality and tactical intelligence, two qualities essential to war.

Ku is not limited to war. He also symbolizes virility, fertility, and the protection of communities. Thus, he occupies a central place in the daily life of ancient Hawaiians. War chiefs, in addition to seeking his favor on the battlefield, also asked him to ensure the continuation of their lineages and the prosperity of their lands.

Furthermore, Ku is linked to the sea. Fishermen pray to him to ensure abundant catches and to protect their boats. This connection with the sea demonstrates Ku’s versatility, capable of influencing both conflicts and natural resources.

His worship is manifested through temples, called heiau , and ceremonies including songs, dances and sacrifices. Ku thus embodies an omnipresent god, both in wars and in the protection of Hawaiian communities. Learn more about Ku, god of war in Hawaii.

Tūmatauenga

Tūmatauenga is one of the principal gods in New Zealand Māori mythology. He is often considered the god of human conflict. He embodies the warlike and destructive aspect of humanity, symbolizing violence, war and struggle. Tūmatauenga, literally “the heart of man” or “the fighting spirit”, plays a central role in Māori stories as a deity of battles and clashes.

In Māori cosmogony, Tūmatauenga is the son of Ranginui, the Sky, and Papatūānuku, the Earth. His conflicts with his brothers, especially Tāwhirimātea, the storm god, reflect the constant struggle between the natural elements and humanity. While his brothers choose to appease conflicts, Tūmatauenga is distinguished by his willingness to fight and conquer. This behavior makes him the protector of the Māori martial art, the “haka”, and of warrior practices.

However, Tūmatauenga’s power is not limited to destruction. His presence is also a reminder of the need for strength and courage to overcome obstacles. He thus symbolises resilience in the face of challenges. Māori honour Tūmatauenga to achieve victory in war, but also to strengthen their resolve in the trials of daily life. His worship highlights the importance of finding a balance between strength and wisdom, while respecting ancestral traditions.

Thus, Tūmatauenga embodies not only anger and violence, but also discipline and survival.

*

In conclusion, these deities illustrate how cultures around the world have often personified war, each with its own characteristics, either related to violence, destruction, or sometimes, to wisdom, justice and protection. Finally, they give us indications on the place of war in each civilization.

Read also Ares and Athea, gods of war.