In Études sur le combat (Studies on Combat, 1880, posthumous), Colonel Charles Ardant du Picq (1821–1870) sets out to base his analysis on soldiers and combat. He takes them as they are in order to determine what is realistically achievable in war.

Indeed, what can be conceived in theory or practiced in maneuvers is not always feasible in combat. This is due to that “primary instrument of war”—the human being—and the supreme emotion in war: fear.

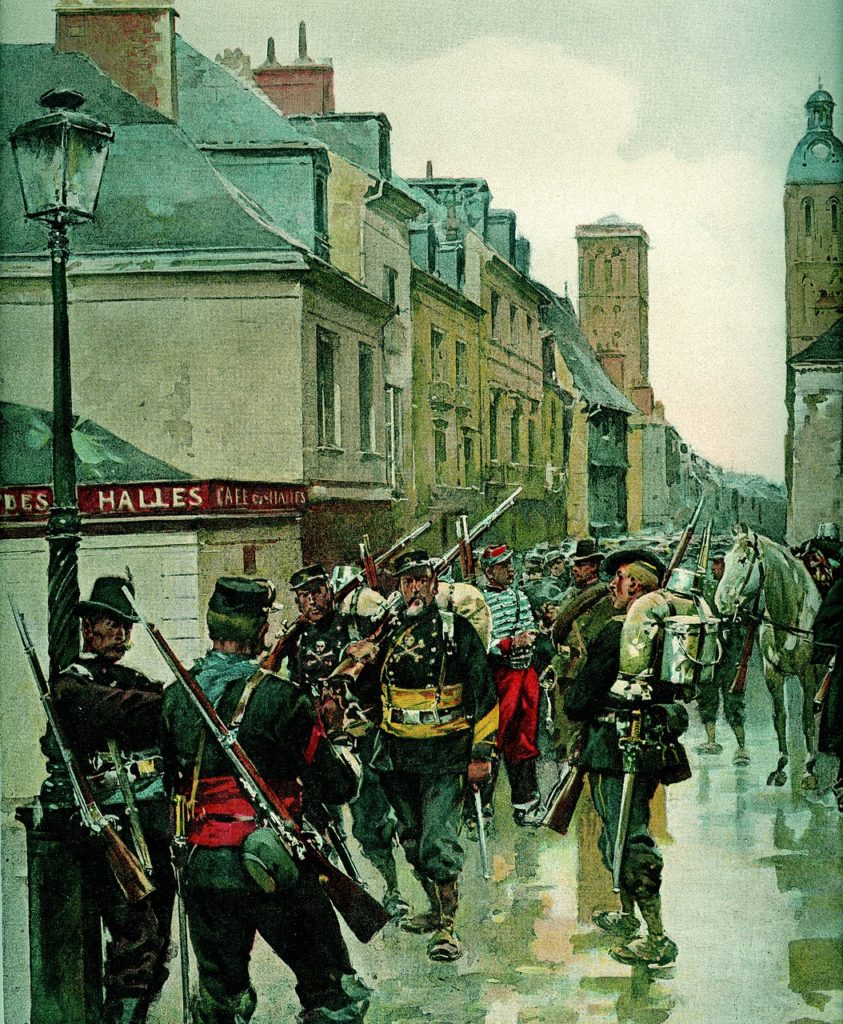

Ardant du Picq analyzes ancient wars, particularly the tactical formations of the Romans, before dissecting 19th-century combat.

Morale is the Key Dimension of Combat

For Ardant du Picq, morale is the key dimension of combat. Consequently, all attempts to approach war mathematically are futile.

He observes that in combat, gunfire is not very effective. Studies of the time showed that it took approximately 3,000 rounds to wound an enemy. This was due to the conditions of combat such as the smoke from weapons and, above all, fear. Soldiers would fire quickly and without aiming, creating the illusion of safety and helping to forget the danger. In many ways, this has not changed. He notes that the fire from skirmishers, who were less exposed because they were dispersed, was far more effective than that of battalions.

Physical fire has less impact on the enemy than movement. Movement brings the psychological threat of an impending clash, causing the weaker-minded to break. Ardant du Picq analyzes cavalry and infantry battles to show that hand-to-hand combat almost never occurs. He demonstrates that the unit with the weaker morale, often the one that must withstand the shock, will turn and flee at the mere prospect of physical contact with the enemy.

Discipline According to Ardant du Picq

Under these circumstances, how can soldiers be kept in combat? Only discipline makes this possible. In Studies on Combat, discipline can resemble mutual surveillance between soldiers or what we might call the social pressure of the unit. The author notes that punishments allowed at the time were no longer sufficient to keep troops in line, and a different motivator was needed.

Discipline, in fact, should not be understood as merely obeying orders without question, but as what enables soldiers to stay with and for their comrades in situations where instinct tells them to flee.

Ultimately, military organizations and command systems are, above all, mechanisms for managing fear.

“The combatant is flesh and bone, body and soul, and no matter how strong the soul, it cannot so dominate the body that there is no revolt of the flesh and disturbance of the mind in the face of destruction.”

— Colonel Charles Ardant du Picq,

Read also :